First to Draft

On the contingency of text

Whether it is a statute, a regulation, a contract, an insurance policy, or a protocol, the first to put words to paper frames the conversation about the artifact going forward.

They set the topics to be considered, the terms in which they are considered, and the boundaries of the conversation itself. These decisions set the initial conditions for the discourse that follows. In doing so, they constrain not only what can be said, but what can plausibly be meant.

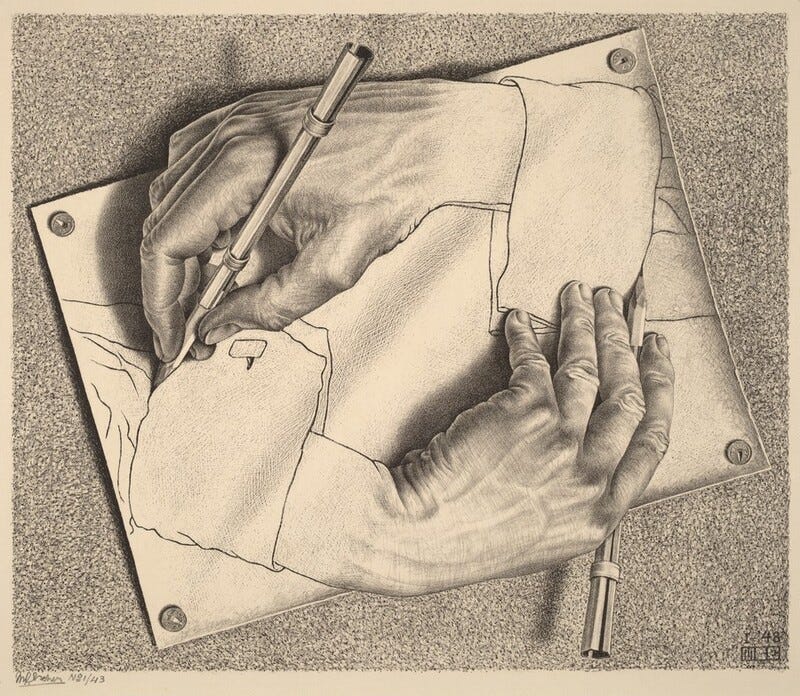

What is most interesting about this power of the first to draft is that those who revise the artifact often forget its contingency. The substrate is treated as a given, a prior, something that is rather than something with a history.

Before the first draft, the space of possible meanings for a work is endless. After the first draft, that space is tightly constrained. This discrete act marks the transition from a state of open possibility to one of bounded interpretation. After the draft exists, disagreement tends to occur inside the draft’s assumptions, rather than about them.

Who wrote it and why? What implicit philosophy motivates it? What questions does it take as foregone conclusions? What might it have asked, but did not? What other ways of arranging it may have been considered, but were ultimately excised? How does all of this affect how, or if, I should engage with it?

Accepting the initial framing of a work is a decision, not a necessity.